UPDATE (June 20, 2022): My thinking has developed since I originally published this piece, and I encourage you to listen to this episode to learn more. In sum: I think I’ve assumed too much in describing the police actions on that day as stemming from cowardice. While this may be true, the fact pattern as it is evident to me today, almost one month after the shooting, does not unequivocally support this assertion. It is evident to me that the police were completely ineffective and at least grossly negligent (where was the master key?!). I’ve left the original piece unchanged in its entirety below.

For more, listen here:

He thought how "Jack," cold-footed, useless swine,

Had panicked down the trench that night the mine

Went up at Wicked Corner; how he'd tried

To get sent home; and how, at last, he died,

Blown to small bits. And no one seemed to care

Except that lonely woman with white hair.

-Siegfried Sassoon, The HeroAfter the 2012 Newtown school shooting in which a lone gunman massacred 26 children and staff, NRA President Wayne LaPierre solemnly intoned, “the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” This was perhaps a defensible claim ten years ago, but it isn’t now. Scot Peterson, the armed security officer at Parkland High School in Florida who did nothing while a shooter went on a 2018 violent rampage through his school, is facing trial on charges of child neglect this fall because of his inaction. (Peterson, to this day, insists he did the right thing, and hosts freelance reporters in his home so that he can share his version of events from the comfort of his TV recliner.)

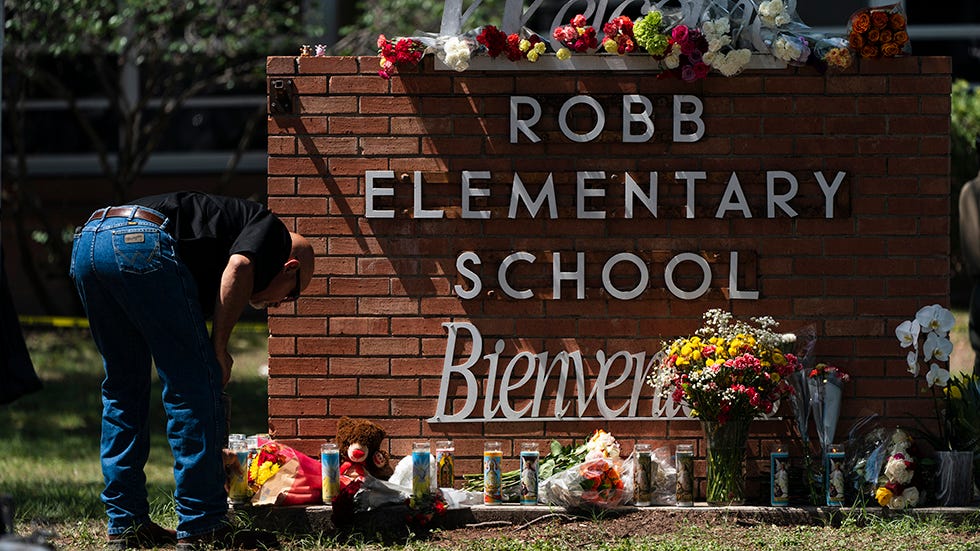

And now over a dozen officers from the Uvalde Police Department, in a carbon copy of Peterson’s performance, loitered outside of an elementary school while knowing that a gunman was inside shooting children. There are plausible explanations for what led the gunman to do what he did: easy access to firearms, where even common sense rules are flouted and ignored; an epidemic of mental illness in young people; a popular culture that glorifies and cultivates violence; the disappearance of strong families and, with them, of strong parental role models. Each of those explanations can help us understand the shooter’s motivations.

What is harder to understand is why these fully armed police officers did nothing for so long. Were they unaware of what was happening inside the building? Were there too few of them? Were they unarmed? Unequipped? The answer to each of those questions is an emphatic “no.” There were nineteen heavily-armed police officers outside of the school who for over an hour let a gunman impose his sadistic will on schoolchildren while children inside were calling 911 repeatedly. Why?

A review of the timeline may help to illustrate the relevant facts at hand. Based on the good journalistic efforts of folks at the Texas Tribune, we know that by 11:30am on May 24th, 911 dispatchers received at least two separate phone calls reporting a gunman outside of the elementary school. One of these calls was from a teacher at the school. Three minutes later, the shooter entered the school and fired at least 100 rounds into two connected classrooms. Only two minutes after that, at 11:35am, the Uvalde police entered the school but immediately came under gunfire from the shooter and beat a hasty retreat. At this point, the police officers issued a radio call for additional resources: “tactical teams, equipment, specialty equipment, body armor, precision riflemen, and negotiators,” according to the Texas Department of Public Safety (TDPS).

By 11:54am, twenty-one minutes after the shooter entered the school and started shooting, parents were in the area pleading for police to enter the school or to be allowed to enter it themselves to bring their children to safety. At 12:03pm, a student called 911 from inside the school. Between then and 12:50pm, students made six separate phone calls to police. In the final phone call, at 12:47pm, a student pleaded, “Please send the police now.” Finally, at 12:50pm, agents from a Border Patrol Tactical Unit killed the gunman. This was 35 minutes after the Border Patrol unit arrived on scene and one hour and fifteen minutes after Uvalde police arrived on scene.

It may be worth a brief pause to reiterate a few basic facts. First, this was an elementary school, not an army barracks. The people inside were not highly trained killers able to improvise and defend themselves. They were schoolchildren between the ages of 5 and 11, and their schoolteachers. Second, of the one hour and seventeen minutes that the shooter was inside the school, there was no law enforcement presence on scene for only two of those minutes. Finally, at no point did law enforcement officers have any reasonable basis for the belief that the children in the school were “no longer at risk,” as the TDPS has asserted was the belief of the on-scene commander; in fact, quite the opposite is true.

So again—why did the police wait so long? The answer is inelegant in its simplicity: they did nothing because they are cowards.

—

C.S. Lewis’ The Abolition of Man starts with a reflection called “Men Without Chests.” In it, Lewis issues a scathing review of the modern educational system, which severs the head from the heart, and results in atrophy of the intellect and a corresponding inability to cope with the demands of a virtuous life:

It still remains true that no justification of virtue will enable a man to be virtuous. Without the aid of trained emotions the intellect is powerless against the animal organism. I had sooner play cards against a man who was quite skeptical about ethics, but bred to believe that ‘a gentleman does not cheat’, than against an irreproachable moral philosopher who had been brought up among sharpers.

In battle it is not syllogisms that will keep the reluctant nerves and muscles to their post in the third hour of the bombardment. The crudest sentimentalism . . . about a flag or a country or regiment will be of more use . . . The head rules the belly through the chest—the seat, as Alanus tells us, of Magnanimity, of emotions organized by trained habit into stable sentiments.

Let us now return to the situation at hand. The police arrive at the scene of an active shooting at an elementary school. They have two options: either wait for greater clarity, personnel, and equipment, or act immediately to apprehend the shooter. This is the problem as mans’s intellect evaluates it: Which course of action maximizes the chance of mission success?

But of course in this framework, the “mission” is not an act of heroism but rather an abstracted bureaucratic concept devoid of interpersonal valuation. It is something that earns a promotion rather than a place in the pantheon. So when the on-scene commander asks himself this question, he sees sums and figures, worked out on a risk-balancing worksheet: how many bullets does an AR-15 hold? How many bulletproof vests do we have? How many entrances are there to the school? How many children are inside? Each of these can be a good question to ask, but only if the question-asking leads to action and not some vicious multivariate analysis of stochastic inputs. That is the job of an insurance adjuster, not a police officer.

On the other hand, the appetite of man (Lewis’ “animal organism”) asks a different question, because it is always interested in self-actualization, in maximizing its own potential, and in preserving its own life: Which course of action is most likely to preserve me? This is a helpful instinct—we would die if we did not feed ourselves—but when heroism is called for, it is generally unhelpful. The appetite is pure ego, and as such, is incapable of selflessness. So when offered the chance to storm a school with a gunman hiding in a classroom somewhere, the appetite forcefully declines.

Taken in turn, one can see the internal coherence to each argument: the first strictly logical (although not reasonable), and the other strictly appetitive. But still there is something here that doesn’t sit well with us. Indeed, something in the decision to wait outside the school at once nauseates the stomach and spins the head.

This is because of the chest—the part of us that loves and fears, that moderates the head and the belly—tells us with conviction that no amount of personal risk can justify inaction in the face of the slaughter of innocents. You don’t have equipment? A hero would go in with his fists, determined to rescue the children or die in the attempt. Your supervisor hasn’t authorized an entry? Bureaucracy be damned—there are children inside. (With this level of excuse-making, I’m surprised that the police officers weren’t loitering outside of the school in KN95 masks.)

But a man without a chest doesn’t have this sort of conviction. When faced with a choice between life and death, he can only fall back on his appetite or his intellect. This is why headlines like “Texas police chief who delayed response did active shooter training in December” make perfect sense. Of course he did. He’s a bureaucrat; a cog in a machine that simulates valor but, more tellingly, valorizes simulation. Can any number of PowerPoint slides turn a coward into a hero?

—

It is no surprise that cowardice runs rampant among us. Even our supposed heroes—Superman, Iron Man, The Dark Knight—come to us in haze of ego and moral ambiguity. Runaway CGI has given Superman a knack for razing cities. We make our heroes fight wars with each other because we find it funny. We even give one of the most profound anti-heroes of all time a backstory because we need to impose process on his randomness and interpret his chaos as, in fact, order in disguise. And even this anti-hero’s foil is unspared—Batman is portrayed, in the New York Times’ review of the latest installment, as a “grouchy and dyspeptic” figure who shows that “the path out of nihilism is through it.” If there are any heroes among us, we don’t know who they are. (This, by the way, explains Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarok, which stands alone in the Marvel canon as a self-aware film that mocks its own genre mercilessly.)

The superheroes’ foibles are not a cause of the Uvalde cowardice, but yet another symptom of our general malaise. In this framework, it is death, not evil, that is the worst foe of humanity. The air we breathe swirls with the miasma of proceduralism, of technocracy, of mechanism. The vacuum in our chest cavity that makes us crumble at the contemplation of our own mortality is the same emptiness that renders us unable to tell stories of heroism or even let our children invent their own. And this thoracic collapse is the real cause of the cowardice.

In a recent reflection at The Atlantic, Elizabeth Bruenig compellingly links the shooting (and so many others like it) to moral decline. But the decline is not simply one of “loose morals” as if one frequented a brothel after the saloon; rather, the decline is in the moral sentiments—our very convictions—themselves: “perhaps the most troubling symptom of our cultural rot,“ writes Bruenig, “is the sense, detectable already in some people, that there simply is no future for us at all.“ This is, indeed, what Lewis is getting at in Men Without Chests:

You can hardly open a periodical without coming across the statement that what our civilization needs is more ‘drive’, or dynamism, or self-sacrifice, or ‘creativity’. In a sort of ghastly simplicity we remove the organ and demand the function. We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.

This is not just a law enforcement problem. The thoracic collapse extends everywhere. We have a police force that cannot police; warriors who fight all the wrong wars; educators who do not educate; governing officials who neither govern nor officiate. There are no heroes among us—or if there are, it’s hard to find them.

We want to believe that the “good guy with a gun” can be the hero we need. But instead, the “good guys with guns”—like the Uvalde Police Department—are the heroes we deserve.

I’m a huge fan of Clive Staples L.

I’m going to go ahead and say what I really think. Men have embraced a culture of non-masculinity. I’m not just talking about guys who self-identify as feminists. I’m talking about men, even married men, who decided decades ago that self-sterilization was a great idea. They’re pleased by their sterile marital relationships which utilize the BC Pill. The hormones aren’t metabolized and pass into the sewers and ultimately the water table thus gradually feminizing entire regions (see ambiguous amphibian sex organs), early puberty in girls, and decreased levels of fertility even in younger adult males. Bill Gates helped this along by purchasing the patent for a GMO corn in the ‘90s which had the curious side effect of decreasing sperm counts in those who consumed it. He then purchased a chunk of Monsanto to produce it. Have some Fritos, kid. But men now demand their partners be sterile too. How many couples dare walk down the aisle without an IUD on board or the Pill in the carry on luggage? Few if any. Men have surrendered the inherent power they had because they could then have fewer financial pressures and improve their living standards. There’s no increase in “happiness” after the measures are in place however. Couples who cohabitate have higher rates of divorce. The Pill makes women less sexually attractive (look it up). Abortion makes women much more suicidal—even in cases of rape (see the stats from Scandinavia where such things were tracked). The entire feminist agenda and its fellow travelers the LBGTQ+++ ever-expanding menu hasn’t led society to any higher function, lifespan, cohesion, unity, or anything else that can be called an unqualified benefit. Now we see that nobody can define what a woman is, even SCOTUS justices, but we all know what a police “person” is not. They’ve had the testicular fortitude trained (or bred) right out of them. One of my adult sons told me recently that he didn’t “give a shit” about empty grocery shelves or high gas prices because Amazon Fresh always has what he wants and he doesn’t drive (he’s in DC) so “it doesn’t affect” him. He doesn’t care about gun rights because he doesn’t need a gun [yet?]. He doesn’t care about anything which doesn’t directly affect him. How did my kid get this way? How did the kid who was pushed in a carriage by me across from the abortion clinic while I prayed, and who filled plates at the soup kitchen all through high school become a disaffected thirtysomething? “Not my problem” he says. The cops in Uvalde held back the parents whose children WERE affected, but because their own kids were safe elsewhere they waited for the experts and restrained the desperate parents-many of whom were women. Are these men who shoot their weapons in video games? While eating Gates-corn Doritos, while relying on their wives to not burden them with “unexpected” products of their manhood? Likely he only imagines himself capable of fathering children. But it would be “irresponsible” to do so anyway.

On the way to His death, Jesus predicted that a time would come when sterility would be called a blessing. We’ve been in that time for a hundred years already.